Recent advances published in the American Journal of Human Genetics highlight a pivotal shift in how scientists describe human populations in genetic studies — moving away from outdated racial terms toward more precise and meaningful descriptors like ancestry and ethnicity. In deepening our understanding of human genetic variation, language matters — both scientifically and ethically.

For decades, human genetics research sometimes relied on broad, socially loaded terms such as “race” or “Caucasian.” However, analyses tracking terms used in AJHG articles over time show a clear decline in the use of “race” and a rise in the use of labels like “African,” “European,” “Asian,” “ancestry,” and “ethnicity”. This shift reflects a growing recognition that continental labels and ancestry descriptors are more biologically and socially meaningful than simplistic racial categories.

This transition is not just semantic. Accurate terms improve how we design studies, interpret results and communicate findings — especially in genetics and genomic medicine, where variation is often deeply structured by geography, migration and population history rather than socially constructed groupings.

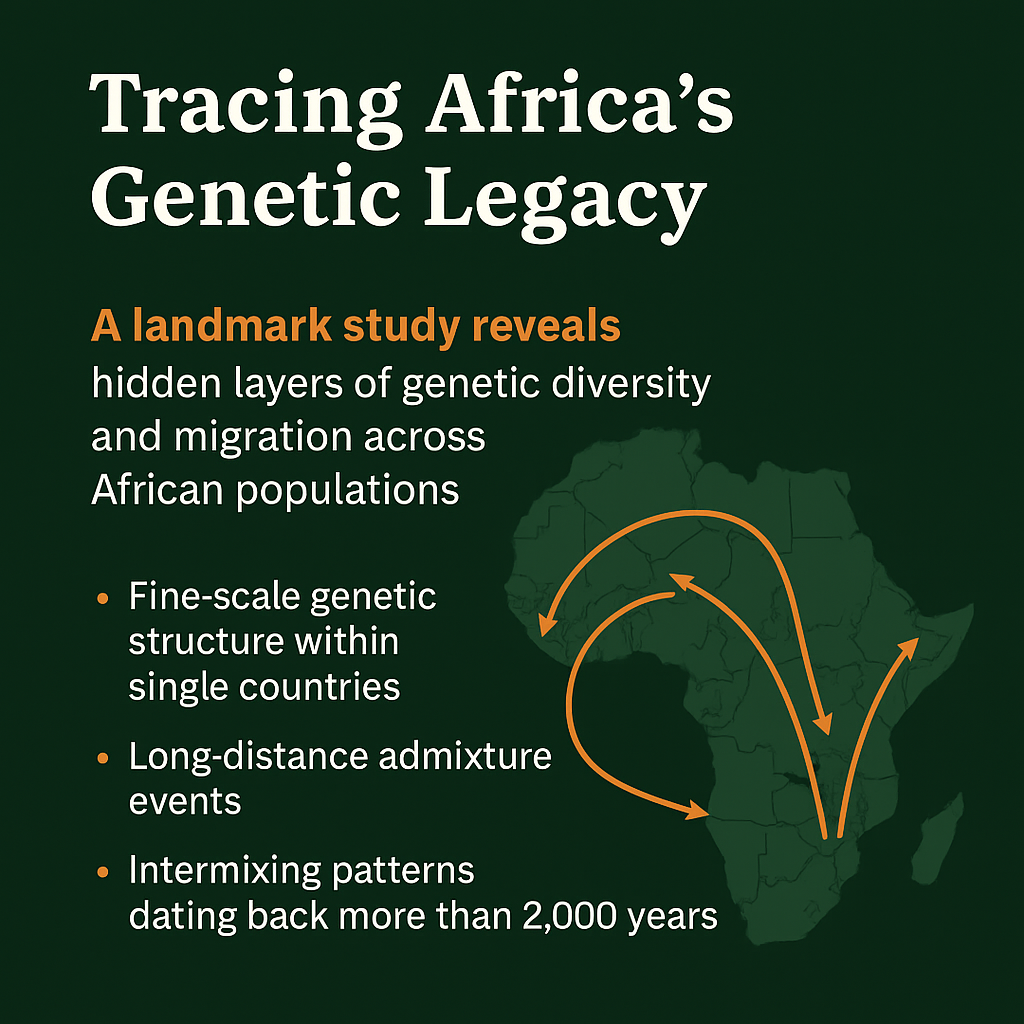

For a company like MyAfroDNA, this conversation underscores why African-centred genomics must be anchored in scientifically precise and culturally respectful language. Africa is the most genetically diverse continent on Earth, and understanding its genetic variation requires nuanced, context-specific frameworks rather than broad, imprecise categories.

By advocating for the use of ancestry and ethnicity labels rooted in deep genomic data — rather than traditional racial descriptors — the field is moving toward more accurate, inclusive and equitable genomics research. This evolution aligns with our mission: to enrich African genomic representation, empower informed interpretation, and advance science that reflects real human diversity.